On 21 October 2022, Austria, on behalf of 70 states, delivered a joint statement on Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems (LAWS) at the 77th United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), during a debate on conventional weapons. Among others, the document mentions that these states

recognise the importance of focusing efforts in particular on elaborating the normative and operational framework regulating, where appropriate and necessary, autonomous weapons including through internationally agreed rules and limits.

Also in October, the UN Human Rights Council (HRC) adopted a resolution on “The human rights implications of new and emerging technologies in the military domain”, which

Requests the Human Rights Council Advisory Committee to prepare a study examining the human rights implications of new and emerging technologies in the military domain, while taking into account ongoing discussions about the applicable legal framework, and to present the study to the Human Rights Council at its sixtieth session.

Given that the global debate on LAWS has been almost exclusively taking place within the framework of the United Nations Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (UN CCW) since 2014, these recent developments are significant. In particular, the UNGA joint statement and HRC resolution raise the question of whether the discussion is moving out of the CCW forum.

The CCW’s main goal is to “ban or restrict the use of specific types of weapons that are considered to cause unnecessary or unjustifiable suffering to combatants or to affect civilians indiscriminately”. The Convention has often been criticised for being “weak” and failing “to progress the law related to weaponry in any substantial ways”. It has been called an “incubator” of good ideas, partly because the forum takes decisions by consensus, which can be defined the absence of objection, but is often de facto treated as a veto. This practice has led to many situations of stalemate, and the discussion on LAWS has been no exception. With the ongoing impasse, some campaigners and experts have called to pursue regulation and prohibition of autonomous weapons in another setting. To what extent can we expect a future outside the CCW for the LAWS debate?

Background on the LAWS debate

Researchers and scientists such as Jürgen Altmann, Noel Sharkey, Robert Sparrow, and Peter Asaro have been warning about the implications of autonomy in weapons systems since the 2000s. In 2009, the International Committee for Robot Arms Control was established and called for “discussion about the establishment of an international prohibition on autonomous weapon systems”.

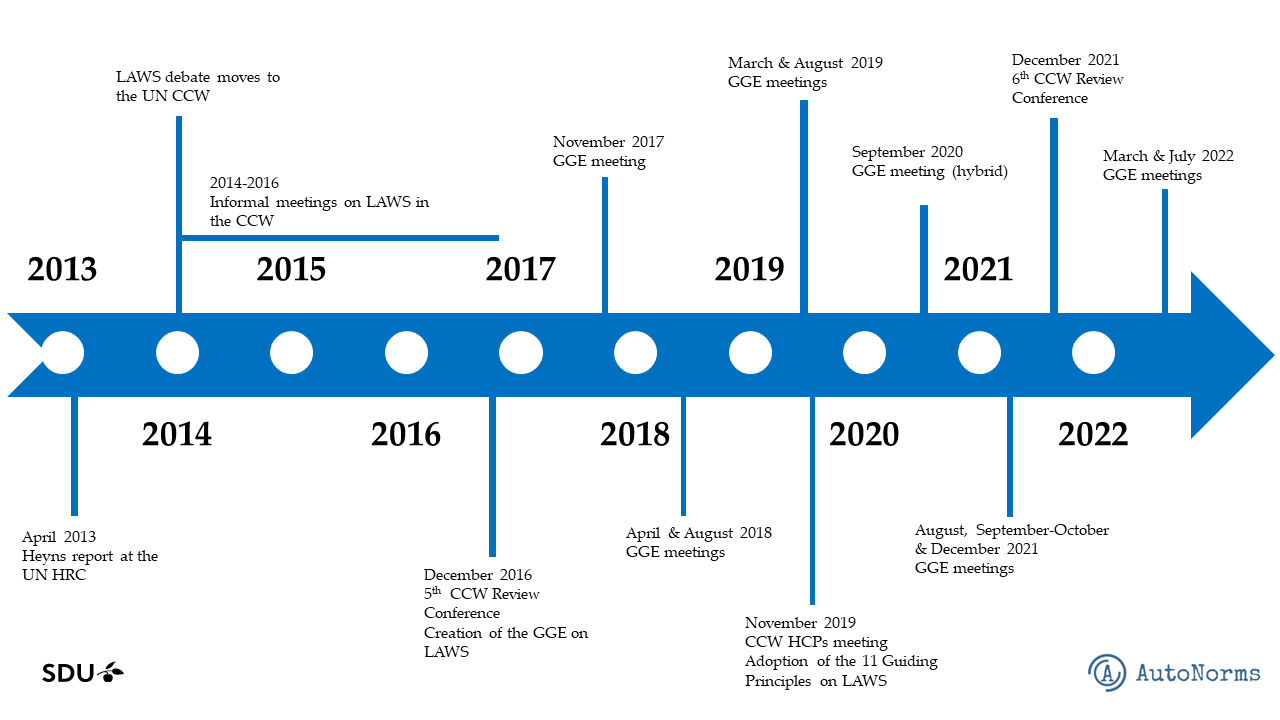

The first international forum to host a debate on autonomous weapons was the UN HRC. In 2013, the late UN Special Rapporteur Christof Heyns submitted a report to the Council, highlighting the legal and ethical issues raised by “lethal autonomous robotics”. The report invited the High Commissioner for Human Rights to “convene, as a matter of priority, a High Level Panel” of experts with a mandate of proposing “a framework to enable the international community to address effectively the legal and policy issues arising in relation to LARs”. The next year, states decided to pursue the debate on this topic at the CCW. After a series of informal meetings, a Group of Governmental Experts (GGE) on LAWS was established within the CCW in 2016.

Although states parties managed to agree on a set of non-legally binding 11 Guiding Principles on LAWS in 2019, the CCW has been facing criticism for its lack of progress in terms of substantive matters, especially regulations of LAWS. States parties to the Convention hold different perspectives on the necessity of new, especially legally binding, measures regulating or prohibiting autonomous weapons. The consensus-based decision-making practice has made it particularly challenging to move forward.

At the latest GGE meeting in July 2022, the substantive discussion has once again been delayed by procedural debates, including on the participation of civil society, to which Russia was opposed. Civil society groups said that GGE meetings this year have “shown the limits of what can be done in the CCW”. In recent debates and publications, the UNGA, another UN forum, or an independent process have all been discussed as options for alternative ways of moving towards the path of legal norms on LAWS, especially as most of them would not require consensus-based procedures.

The CCW vs. the UNGA

The 2022 UNGA statement is broad and repeats some themes of the 11 Guiding Principles, including commitment to International Humanitarian Law and

the necessity for human beings to exert appropriate control, judgement and involvement in relation to the use of weapons systems in order to ensure any use is in compliance with International Law, in particular International Humanitarian Law, and that humans remain accountable for decisions on the use of force.

A key point, however, is that the statement is supported by both states which have argued for a legally binding instrument banning LAWS and states that have been skeptical or opposed towards legally binding measures. As pointed out by some civil society actors, the fact that the statement has approval from across the spectrum signals that an agreement on the necessity to move forward can be reached despite the differences which have been stalling the CCW process.

The declaration makes clear that there is no intent to launch a separate process. Its supporters intend to pursue work on potential LAWS regulation within the CCW. The document admits that “it has proven difficult to translate progress made in the CCW’s discussions into further concrete outcomes”, but in terms of developing a normative framework for LAWS, it calls “to continue to proactively engage on this important issue, including by urging States to make progress towards an outcome at the GGE”. Overall, its main message is to signal the political will to pursue the discussions despite the circumstances of the GGE.

However, at a time when the GGE process has been stalling, it is worth keeping the UNGA path, and particularly its “normative power”, in mind. The process leading to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), for instance, went through a UNGA open-ended working group which recommended negotiations on a legally binding ban of nuclear weapons in 2016. Signed in 2017, the TPNW then entered into force in January 2021. The Treaty remains a matter of debate among policymakers and the expert community given that states known to possess nuclear weapons or states under their protection are not parties. Although it is not universal, the treaty is still argued to have normative value. It shows the will to set a strong norm on banning nuclear weapons and a political and legal direction towards the universalization of the norm.

Considering this experience, there are several points to consider for potential LAWS regulations. The UNGA could be a viable path for a vote on establishing a mandate to begin negotiations on LAWS regulations. This could take the form of both prohibitions and regulations, depending on the type of autonomous weapons. Although resolutions adopted at the UNGA are not legally binding, this forum has been highlighted as having potential to make progress in setting norms on LAWS, especially given that a vote there does not require consensus.

At the same time, there is no guarantee that key issues of contention at the CCW, such as the definition of LAWS or the role of the human element, would be resolved elsewhere. They could simply be transferred to another forum. Political differences would also remain. States which are against new instruments (often developers of LAWS-related technologies) are unlikely to sign up to legally binding measures, whether at the GGE process or elsewhere. Russia, among others, has made it clear that it wants the debate to stay at the CCW, not least because it considers consensus decision-making as a veto power to protect its interests. It is doubtful whether Russia, Israel, India, or the US would participate in another process. And as with the TPNW, US allies might feel pressured to not move forward with regulation if the US rejects this option and implicitly forces its allies to choose between humanitarian concerns and strategic/alliance interests.

Yet, moving forward with legal norms can be beneficial even if major developers or ‘great powers’ do not sign up to it immediately. As AI expert Toby Walsh from the University of New South Wales argues, no regulation or prohibition of LAWS will be perfect. But progress will require cooperation, and both the UNGA statement and HRC resolution can be interpreted as signals that this could be possible, including outside the CCW.