By Paolo Franco and Guangyu Qiao-Franco

Military-themed videogames are not only popular among consumers, but they also generate considerable commercial interest. The Call of Duty series, for example, is one of the best-selling videogame franchises of all time, having sold 425 million units and earning $30 billion in revenue since its debut in 2003. These numbers are evidence of the ability of videogames to become constant features in the lives of millions. As military-themed videogames have reached ever-wider audiences, the artificial intelligence (AI)-enabled drones, tanks, and robots increasingly presented in these games have also entered the public’s consciousness.

Indeed, AI-enabled weaponry with limited human control has become integral to the stories and worlds that many military-themed games build while exploring a variety of potential contemporary and future warfare scenarios. As the public becomes engrossed in such popular culture portrayals of weaponized AI, they may grow accustomed to new human-machine relationships through learning that takes place in virtual environments. While international debates over military applications of AI remain limited to elite and interstate settings, international humanitarian law, especially the Martens Clause, highlights the importance of ‘public conscience’ as the final perimeter in safeguarding humanity in warfare technology applications. In light of our interest in military-themed videogames, it is possible that such games become a domain in which debates on AI-based weapons may be rendered accessible to the public.

But can videogame portrayals of weaponized AI inform the public sufficiently of the risks and potentials of real-world applications of AI? And if yes, would this be sufficient to allow the public’s positive involvement in political discussions? In this blogpost, we explore these important questions by detailing the conflicting presentations of weaponized AI as both ‘insurmountable enemies’ in game narratives and ‘easy targets’ in gameplay—an inevitable paradox that occurs when developers offer consumers easier gameplay difficulty settings, more futuristic and flashy AI weapons, and first-person perspective ludic experiences. We discuss such portrayals’ limitations that give mixed signals regarding human-machine interaction, building on our recent study published in Security Dialogue.

Canine robots and androids and drone swarms – Oh my!

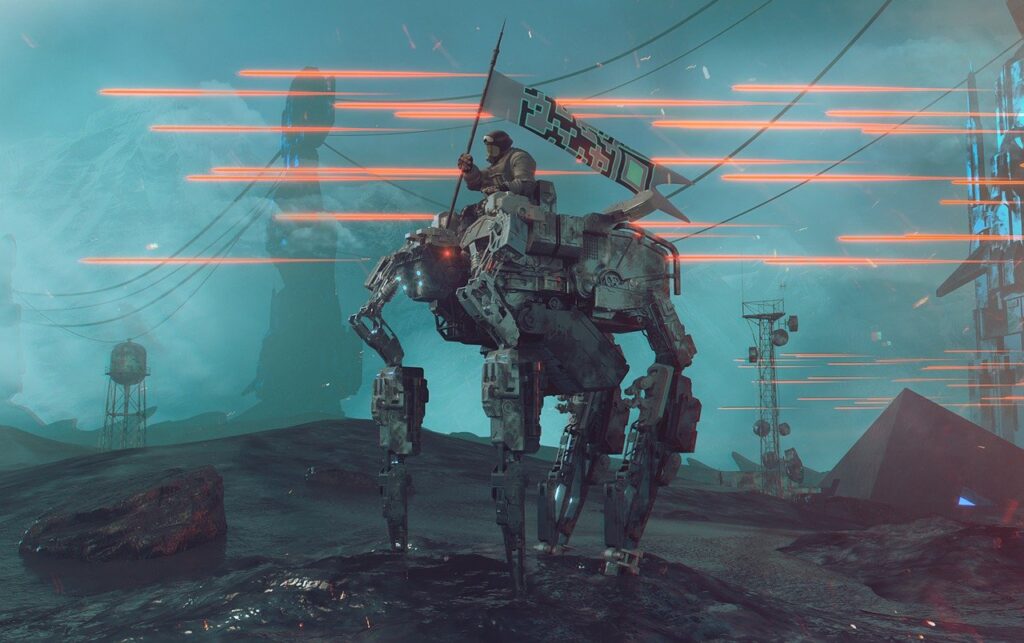

Since the 2010s, military-themed videogames have featured autonomous weapons systems integrating AI. Robots reminiscent of Boston Dynamics’ BigDog, for instance, stalk Arctic battlefields in Ghost Recon: Future Soldier. Similarly, Call of Duty features android combatants that dismember human soldiers in Black Ops 3 and drone swarms that haunt a futuristic 2054 Seoul warzone in Advanced Warfare. These AI weapons are paraded as existential threats to humankind in videogame narratives, intended to be warnings of dystopian futures by game developers. Although prior academic studies suggest that pop-culture portrayals like these can shape public understandings of AI weaponization, our research on the production and consumption of military-themed videogames suggests that this influence has its nuances and limits.

In our study, we conducted six months of netnographic fieldwork in relation to 19 military-themed videogames and analyzed our data through an “actor-network theory” lens. As part of our fieldwork, we watched dozens of hours of YouTube “Let’s Play” footage in which consumers played military-themed videogames and commented on their gaming experiences in real-time. We moreover watched videogame trailers and reviews, read press interviews by developers, and immersed ourselves in the imagery and texts of fan Wiki pages, Reddit forums, and gaming media stories associated with the videogames we studied. It is through this data that we analyzed how such videogames can shape players’ understandings of weaponized AI.

Based on our data, we find that videogames are a common way in which many consumers first learn about AI’s potential applications in warfare. In these instances, players are confronted with realizations that future battlefields can be made more deadly by AI weapons and that these conflicts can more easily reach their doorsteps. Haunting scenes of cities and suburbs engulfed in flames as ‘insurmountable enemies’ the likes of animal-shaped robots, android soldiers, and drone swarms circling endlessly bring such dystopias to life. This insight echoes prior research that argues that pop-culture can influence public understandings of new political developments (e.g., films, TV shows), including how the meanings contained in such materials can be mobilized to support or oppose the regulation of autonomous weapons.

Ludonarrative dissonance: When narratives and gameplay send mixed messages

However, we also find that what makes a particular form of pop-culture mass-marketable can limit the kinds of critical messages it can offer to consumers. For videogames, mass-marketability relies on how fun they are to play. Games in which enemy AI weapons can easily kill players who are role-playing as human soldiers, consistent with the purported lethal efficacy of future AI-enhanced weapons systems, are often difficult and frustrating. This was a common critique of some of the games we studied by players on online forums and in YouTube “Let’s Play” videos.

Indeed, we observed in our data that developers consequently tone down how challenging AI-based and autonomous weapons are to play against to keep things manageable for players. Notably, we discovered that how challenging these weapons are to fight as human protagonists are governed by videogame difficulty settings. Of which, we found that only the most proficient players choose higher difficulties that approach the envisioned lethal efficacy of weaponized AI to humans. What results from these developer and consumer choices are players becoming able to obliterate scores of AI-augmented robots, androids, and drones with ease. In so doing, AI weapons are rendered into ‘easy targets’—undercutting meanings over how lethal these are supposed to be in the same videogames’ narratives.

Such contrasts between videogame narratives and gameplay is termed ludonarrative dissonance. This term has become a buzzword among videogame critics to scrutinize what sets apart games that are ‘great’ from simply ‘good’ for connoisseur players. Based on our study, however, ludonarrative dissonance may be a needed trade-off for videogames to be mass-marketable and hence profitable to produce for everyday consumers. What this means for academics, policymakers, and others thinking about how the public may learn about the weaponization of AI is that while these games have the potential to raise awareness of the risks and dangers of AI, these messages might be lost on players who simply seek thrilling experiences in which they (and their human avatars) remain firmly in control.

Futuristic and flashier weapons obscure other forms of weaponizing AI

A second finding concerns our observation that more futuristic and flashy AI weapons tend to grab the most attention at the expense of more ‘mundane’ ways of weaponizing AI. That is, enemies such as BigDog-esque robots, humanoid combatants, and drone swarms obscure relatively more mundane weapon systems integrating automation, autonomy and AI, such as air defense systems, drones of the non-swarm variety, and automated sentry turrets that can be integrated into combat vehicles like tanks, planes, and ships.

Based on our analyses, these more mundane weapons systems do not offer as vivid and quick to understand imagery that can grab the everyday consumer’s attention. Far easier to understand, and anchor action-packed gaming stories and experiences, are AI weapons that resemble the infamous Terminator or Boston Dynamics’ BigDog—both staples of contemporary pop-culture when it comes to AI and its envisioned military applications. The issue inherent in our observation is, echoing Charli Carpenter’s work, that audiences may see such threats as too far into the future to warrant any concern or action in the present. As Carpenter suggests, pop-culture producers, and those using such cultural touchstones to inform the public, may need to ‘de-science-fictionalize’ the ongoing weaponization of AI, so audiences take it seriously once their attention is first captured.

From whose (videogame) perspective is it anyway?

A final finding we share from our study lies in considering what kind of videogame mode a portrayal of weaponized AI resides within, and whose perspective a player takes in relation to it. Thus far, we have discussed what is best representative of the vast majority of military-themed games we studied: first-person shooters. In such games, players see first-hand, in an embodied perspective, the world of the character they are playing—a human soldier in a battlefield situation. In many of the games we studied, this first-person perspective translates into going face-to-face with weaponized AI.

As such, the players we observed and the discussions we monitored were oriented around human vs. machine experiences at the individual person level. Rarely did players think about or discuss what AI weapons might mean within larger warfare contexts in which they might become necessary partners and tools on battlefields. Even far more distant of a thought are how the existence of AI weapons is already altering relationships between states, and how many battles that concern them will play out in international dialogues, forums, and other proceedings by a variety of international actors and stakeholders.

A rare exception were ‘tactical’ videogame modes that enable players to have a birds-eye view of a battlefield while guiding coalitions of human soldiers, vehicles, and robots. Rather than role-playing as a soldier, in tactical modes, players role-play as a military general, and by extension, the personnel and armaments under their command. Rather than simple enemies, AI-enabled weapons are translated into tools and partners that must coordinate with other humans and non-humans on the battlefield. In this way, players not only see AI weapons from more of a strategic military-oriented perspective, but they are distanced from the brutal realities AI weapons can impose on the ground.

Tactical modes, however, were rare in the 19 videogames we studied. Player and media reviews suggest that tactical modes did not appeal to most players who were seeking thrilling action sequences, rather than the ‘chess like’ strategy they instead require. This observation suggests that the market for tactical military-themed games is certainly not close to the scale of the first-person shooter games that have dominated the gaming landscape in the last 20 or so years. In light of our broader focus on fun gameplay as what makes videogames mass-marketable, tactical games that offer different ways to present AI weapons to the public appear limited in appeal and profitability.

Conclusion

Our work ultimately suggests that what makes a particular form of pop-culture mass-marketable and profitable may be at odds with its ability to be critical about a topic and influential on the public. This insight bears implications for other forms of pop-culture beyond videogames and how these might need to balance different commercial considerations with aspirations to inform the public about pressing developments related to the ongoing weaponization and militarization of AI.

Analogous to videogames and fun gameplay, for instance, must late-night satire harmonize informativeness and humor? TV shows like Last Week Tonight with John Oliver or The Late Show with Stephen Colbert certainly need punchlines to call attention to new developments in the weaponization of AI and associated regulatory efforts to ban fully autonomous weapons. But more importantly, could these TV shows play key roles to sustain enough public attention to inform and spark action? Equally, must films abide by a three-act structure with a happy ending for any critical messages they carry to be widely influential? Must a song have a catchy chorus to get its message through? We hope that this blogpost, and our Security Dialogue study, opens doors for future thinking that lies at these intersections between pop-culture consumption, politics, and the weaponization of AI.